We offer this as a roadmap and recipe for our Pacific Rim Park family. It details how to initiate, design, gather materials, and construct other PRP sites. This can also be a guide for any group interested in creating community via the building of a design/build park in any part of the world.

Soon after the birth of the project we called “Pacific Rim Park,” we built its first park in Vladivostok. We all thought it was a one-time, one-off project: a way to get people from San Diego, California, U.S.A., and the countries of Mexico and Russia, to make something together.

After Vladivostok, everybody involved felt we accomplished something special. We reflected on our achievement for a year and thought, “Let’s do another — this time in San Diego!” We had all forgotten the sore muscles, smashed fingers, and month of backbreaking labor that went into the first park, but working on a Pacific Rim Park creates a kind of joyous amnesia.

In the years since Vladivostok, each time we go through the process of identifying a new city to become a member of PRP’s “string of pearls,” we find it both strange and familiar — and the process has definitely evolved during the eight parks created to date. Eventually we hope to create at least one park element in every country that touches the Pacific.

Any Pacific Rim Park site must:

- Be on a Pacific Ocean shore, or a bay or sea directly connected to the ocean.

- Be at the water’s edge like the site in Yantai, or have a strong connection to the sea such as an ocean view, like the site in Tijuana.

- Be on land open to the public for free.

- Have a public agency that both owns the site and commits to maintain it.

- Have a pearl element as part of the design.

- Start with a design that can be both created from scratch and built in a one-month timeframe using the time-tested PRP design/build approach.

- Be a part — an element — of the greater collective Pacific Rim Park concept.

Finding a suitable site

Each project usually begins when a person in a new city or region thinks they should join the PRP family, or when PRP committee members reach out to a city or region with strong potential as a new site.

Each host city needs a person or organization that can be a major advocate for the concept. He/she/they should have both political clout and some form of authority to turn the potential site into reality. PRP has worked with lead partners such as universities (Vladivostok and Kaohsuing), port districts (San Diego), highway departments (Tijuana), foreign affairs offices (Yantai), local city governments (Puerto Princesa), non-governmental organizations (Jeju), and others. These entities use their leverage in the community to get the process moving, but on any journey PRP also enlists the help of many other organizations and individuals. We encourage and demand that there be many stakeholders, and this includes the support and participation of the community that we are encouraging.

After a host city and some key individuals are identified in an appropriate city, we move on to finding a local architecture or design school that would like to be involved. The host city also pinpoints five to ten potential sites for a visiting PRP Executive Committee and PRP artistic director to review and eventually select one. We consider the best time of year to build the park, based both on typical weather conditions and school calendars in the host country. We think about sources of funding, which may include cash contributions, grants, government programs, and in-kind contributions such as donated building materials, hotel rooms, food etc.

At some point a member of the PRP Executive Committee will travel to the host country for an initial visit. We meet with our potential partners in the adventure and explore the schools, possible sites, local materials, and methods of construction that might be involved. The team can make presentations to design school students, appropriate non-profit organizations, and local political leaders who will eventually need to support the design and construction process. Typically, team leaders travel to the host city four or more times to align all parties with the process and goals.

When getting ready to start a park process, we always encounter great skepticism every time! How can we actually design and build something of this scale in such a short time frame? We now have eight great answers to such skepticism: the eight projects you see on previous pages. It’s frightening because each park always has unexpected challenges such as uncooperative weather and delays in materials and equipment deliveries. Team leaders must be nimble and keep the group working, focused, and constantly in a problem-solving mode.

How to approach the design process

Our design process is unique because we do not present a predesign to a city before we start. Local leaders find this difficult to accept, but eventually they realize that PRP is an art project rather than a building. We do, however, share design constraints before we begin the class: a park’s scale, palette of materials, and construction methods. This key step helps alleviate many of the initial concerns of the local authorities.

During the one-week design process team leaders consult with local architects and city planners, keeping them abreast of design thinking, so by the time the group settles on a design for the park there are few surprises for the local authorities. This is a delicate dance between giving the students and artistic director enough latitude to design freely while keeping the local building authorities confident that the final outcome will be in keeping with local safety and other building-code compliances.

Material selection (we think of it as creating the “palette”) is critical for the success of each project. We also prioritize access to necessary construction tools. We research what’s available well in advance, usually on some of the initial visits by the PRP committee, and narrow down our options. This has the benefit of giving the students a limited, well-defined palette to consider in their designs. We try to work with regional materials as much as possible. Also, since we are on or very near the ocean, materials and plants must hold up to a harsh maritime environment. We do not order any materials until after the design is completed. A tight timeline necessitates that materials are easily available and fairly common. Everything must be kept within an overall budget that we outline with the host country prior to the build.

Our design process works well. One person serves as the Artistic Director, and to date on all projects this has always been Jim Hubbell. In the future, there will be others. Joining the Artistic Director is a small team of expert artisans, construction experts, architects, and others. This team has to be able to both facilitate a design charrette (an intense period of design and planning) and a studio experience for the students. They also must be skilled in managing and pitching in during the construction process. Team leaders all “wear many hats,” but one person always has the final say on design decisions: the Artistic Director. This person must be open to all of the students’ input, plus ideas from the other team leaders and host city. The Artistic Director finalizes the students’ creative and energetic work into a design that is beautiful, buildable in a short time frame, and still reflects the students’ ideas: they can truly see their input.

One-third of the students should be from the host city so they can share their intimate knowledge of their city and part of the world with other students and leaders. Two-thirds of the students hail from other countries and see the host city with fresh eyes and the curiosity of a cat. A dynamic design environment soon develops. The design directive for each site centers on asking questions such as, “What does it mean to be a part of the Pacific Family and how does this specific site relate to the Pacific?”

We look for the cultural, geological, human, natural spirit of the site to be revealed to the group, and try to use that information — however ephemeral — to inform the design. We try to find and understand ancient myths in the region and inform the design with history, both human and pre-human. We do not try to build something “of the moment” but hope to express something timeless, grounding, and still open to a visitor’s personal interpretation. This process is both confusing and exciting!

Day by day: a rigorous but exciting design journey

After arrival, but before seeing the build site, we try to bring the group to an inspiring place with great cultural significance. In Yantai we visited a 12th-century palace. We sometimes go to cultural history museums and viewpoints where we can get an overview of the city. By exploring an area together in the very beginning, the team begins to get to know each other fast. We share our life stories and hopes and dreams. We also do some drawing: getting the students “out of their heads” and connected with their hand … and eyes.

On the second day we go to the site for the first time and everyone explores at their pace. Ideally the site’s total land area is much greater than the project’s footprint so that we can have input as a team on selecting the exact location of the built elements. Students must not design anything yet — just take it all in: the smells, wind, sun, views, surroundings, and general feel of the land. One exercise we do as a group before we leave is to bring everybody together and ask them to — on their own now — to silently search for, and finally stand, on an “energy center” ( a place where they initially feel something should be built). This also helps reveal where most of a group of students gravitate to on the site. We’re building a sense of teamwork and commonality.

Back in the studio we begin by having the students draw “what they see and think” — but not a design per se. They’re inputting info and not outputting designs yet, and it’s a difficult assignment. We then go back to making more drawings, still mostly exercises: for example, drawing a sea creature, from their imagination, of course. We then share these with each other. Many show hesitation at this time because sharing your creative work is not always easy, but it’s critical for the process of learning to work together.

In the case of the sea creatures, we put them all on the floor and the group stands around them and makes comments. No one quite knows who drew what creature, so we have fun. Then we ask each student to select someone else’s creature and draw — on that same piece of paper — a home for that creature. Once again we look at these drawings together. Collaboration blooms!

For initial park designs, we ask the students to work alone. Then they share their work with the group, and a collection of ideas and thoughts begins to develop over the course of a few days. This is the last time the students work individually on park design.

We now move students into small groups of two or three, encourage more cultural influences, make more site visits, and explore the local materials we will work with by visiting, for example, a quarry, stoneyard, or other supplier.

We now reduce the number of groups by increasing the design-group sizes. We’re coalescing. Students can change groups, share each other’s ideas, and all ideas generated are everybody’s to use. We have a series of group pinups and discussions. We move on to using more exact site drawings, and the designs develop complexity and sophistication. When we change over from designing in two dimensions to 3-D model making with clay and other materials, the designs transform dramatically because they have to be built at such a small scale.

Throughout the design process we layer in technical information about the site, limitations of materials, and the city’s expectations. More cultural information always needs exploring. Team leaders think about the design constantly, absorbing and learning from student explorations and ideas.

At the end of the sixth day each group presents their models and sketches. We try to bring in outside people for this review. The atmosphere is charged with excitement and satisfaction, so we have a small celebration that same night. We’ve reached a milestone.

On the seventh day we typically give the students the day off for a fun excursion —a beach trip or mountain hike, perhaps. Meanwhile, team leaders stay in the studio and pull together a design. This is a critical moment where the skills of the artistic director and other team leaders coalesce into a final design that is culturally appropriate, beautiful, inspiring, representative of the students’ efforts, and buildable in 20 days by a small army of enthusiastic but woefully unskilled students. But they will learn … and fast!

When we present the final design to the students, we ask them for their permission to proceed. We strive for their buy-in to build as a team. We emphasize that the group’s ideas have been synthesized into something that incorporates much of their design energy, but also has been filtered through the Artistic Director’s mastery and vision. So far, we have always gained approval from the students.

On the last design day, we make a series of construction and presentation drawings. The construction drawing is a classic way to grapple with the upcoming technical challenges. The presentation drawings and models are presented to the local authorities on the eighth or ninth day for final approval. We’re ready to begin site preparation.

Construction begins

We have about 20 days to build the park. A team typically works almost every day — and often overtime — for a month. The build process is intense, grueling, unpredictable, and exciting all at the same time. Typically, we have any heavy equipment do site prep for the first few days. We plot the site, think about where materials will be staged, how construction should proceed most efficiently, and how we are going to bring this park out of the ground and finish it artistically in such a short time. Days on the site run sunup to sundown, with some evening talks and discussions sprinkled in. Having a general contractor or builder as part of the team, as well as some local workers, provides necessary experience.

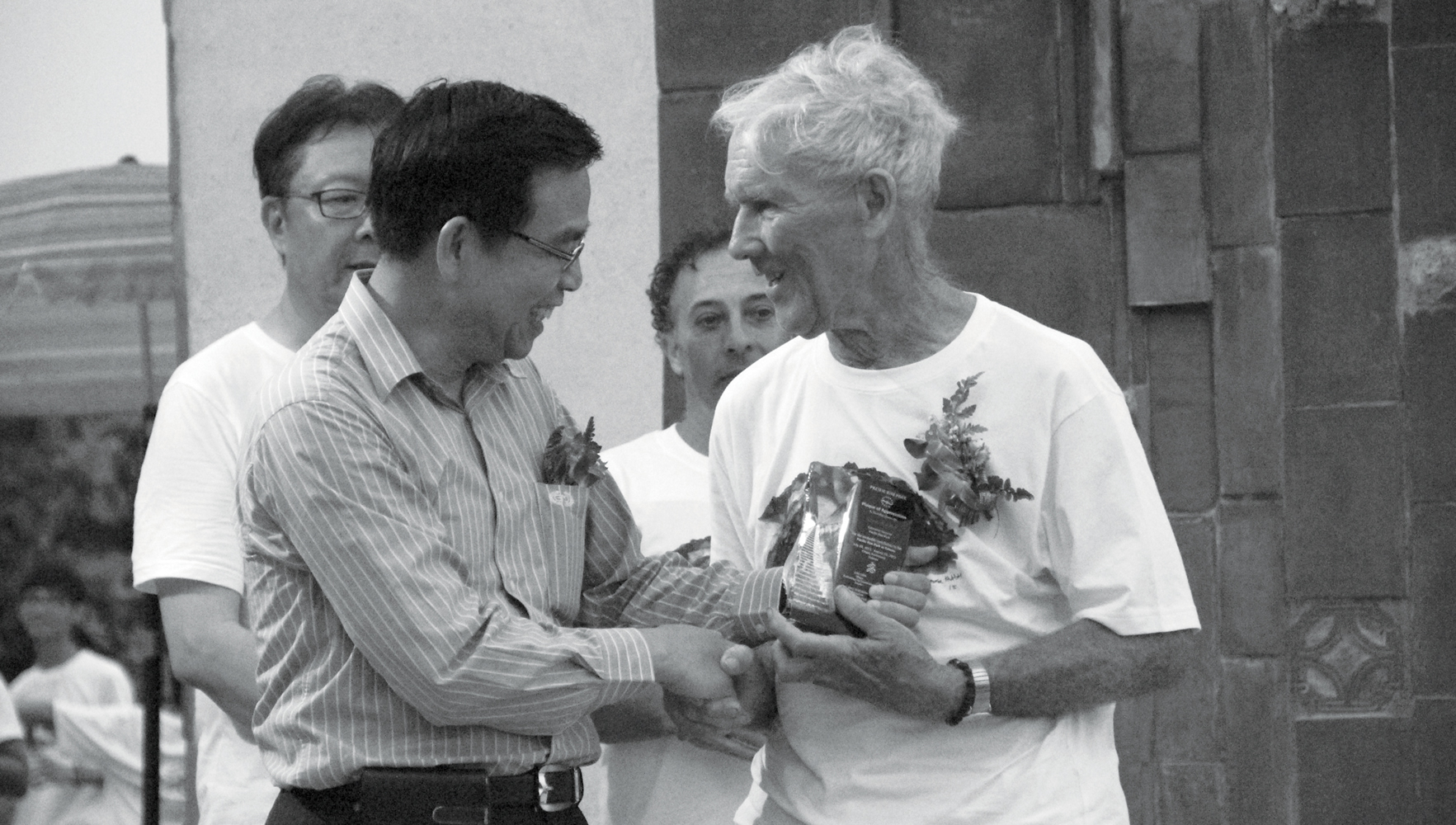

During the last week we get an extra push of energy and expertise by inviting PRP alumni and other architecture students from the host county to help. On the last day we make sure the park is clean and ready for an opening ceremony. We officially present the park to local citizens and to the greater Pacific community. It’s also important on the last day to set aside two hours during which the participants alone can come together and talk about the experience they all just went through, as the closing ceremony and wrap-up celebration leave little time for reflection and shared memories.

On the following day almost everyone leaves for home quickly, like a breeze that blows through a forest. We know we have built something special, overcoming long odds by working together. Everyone can see, touch, and marvel over the product, but the process will last for a lifetime.

In conclusion

We learn lessons from each park that help us with the next project. This process will continue to evolve as we move towards our goal of creating a park in every country. By the time we build the final piece of the overall “Pacific Rim Park,” there may not be one person still involved in one or more of these first eight projects, but the core ideas, beliefs, and methods that make up Pacific Rim Park’s DNA will live on.

Certain core principles have proven to be essential to keeping each project on the right path: we build trust, friendship and community within the group, and keep in mind this is art and not science. There’s no guarantee that the individuals will form a family, so team leaders must be constantly aware of how this critical part of the group dynamic unfolds. The Artistic Director leads while still being open to the ideas and energy of the young designers and anybody else involved with the process. He or she must find a way to take the very raw, sometimes very sophisticated, ideas and thoughts of young designers and coalesce them into a mature final concept. Keeping to the 30-day limit keeps the scale of the parks small and allows for many different types of participants to be involved (and builds their sense of playing a key role). Hardship has its place: the intense physical and mental work required of everyone has a lasting impact, a huge sense of accomplishment.

Over the years physical parks will come and go—structures are actually less permanent than one might think — but what we hope will last and continue to grow is the ever-widening network of friendships and family that someday binds the people of all Pacific Rim nations together for a long-lasting, peaceful future.